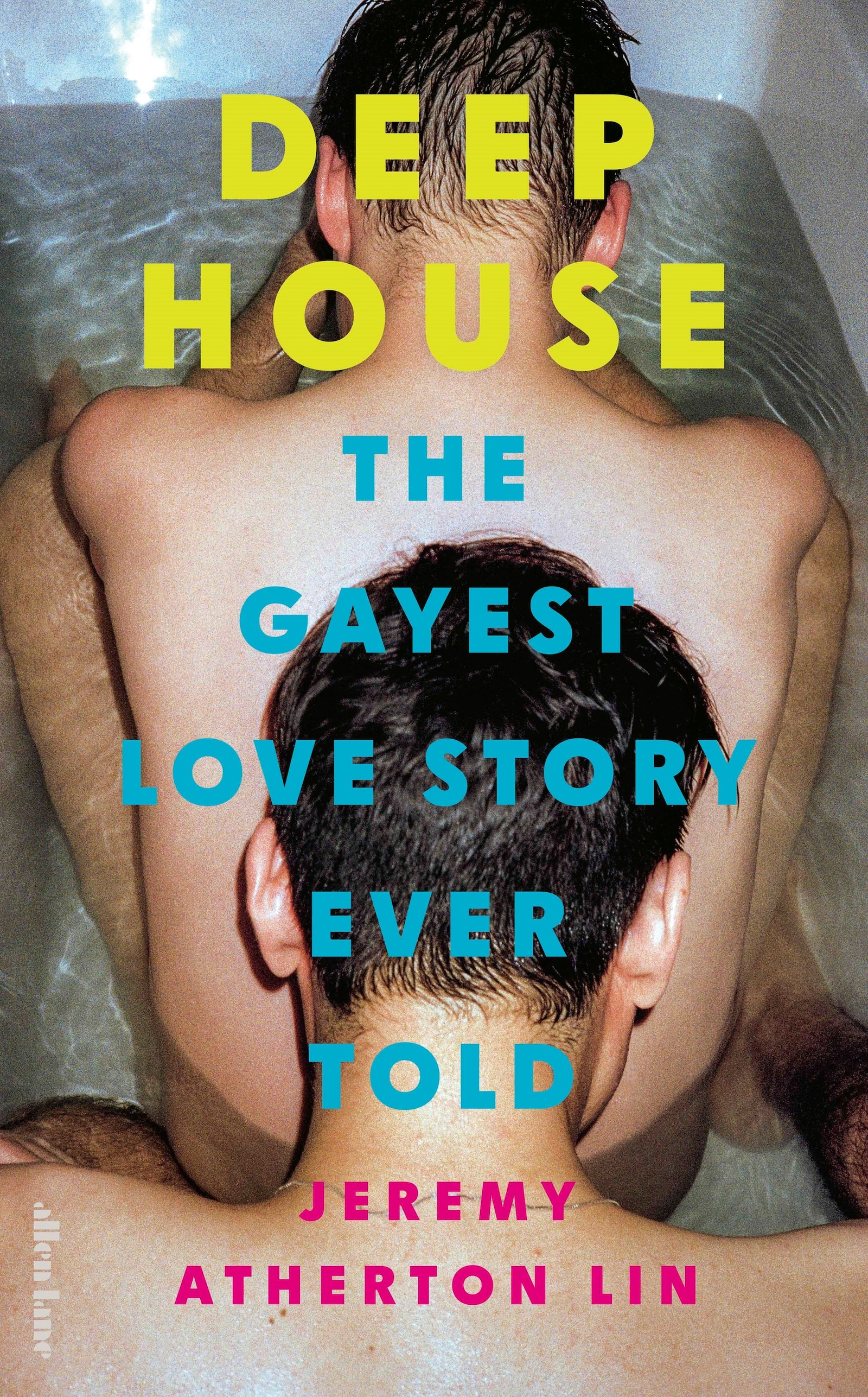

Lead ImageJeremy Atherton LinCourtesy of Allen Lane

Jeremy Atherton Lin’s second book, Deep House, is partly the story of his own relationship. The American writer never names the “sweet, fay, floppy haired” British boy he’s now spent nearly 30 years with, but his crisp prose traces the formative years of their love with affection and intimacy. When Lin and his future husband meet in London in 1996, same-sex marriage remains a pipe dream on both sides of the Atlantic. They want to live together but can’t be legally recognised as a couple in either country, so Lin’s partner joins him in San Francisco as an “undocumented” immigrant. His everyday life is defined by having to fly under the radar: work is cash-in-hand, and accessing healthcare is treacherous.

Lin readily admits it took “a while for me to have confidence that this was a story worth telling”. He pushed ahead because he knew his personal history was never going to “exist in isolation” within the pages. Instead, Deep House is an evocative cultural memoir in the style of Lin’s award-winning debut book, 2021’s Gay Bar: Why We Went Out, which filtered the history of queer venues in London, San Francisco and LA through his own evolving and often ambivalent relationship with them. For Lin, a mixed-race gay man, these spaces didn’t always feel as safe as they should have.

In Deep House, he threads his own lived experience, which is joyful but fraught with risk, with the stories of politicians, pioneers and accidental activists who paved the way for same-sex couples to live together legally. “I felt very confident that I was going to be able to find historical cases about people who had issues with border crossing, invasion of privacy, and really just figuring out a way to be who and where they wanted,” Lin says. He brings up a particularly tragic example: the Supreme Court case pertaining to Clive Boutilier, a gay Canadian who emigrated to the US in 1955 before being deported 13 years later because he was “afflicted with psychotic personality”. Boutilier’s supposed psychosis was simply being a sexually active gay man – these were less enlightened times – so his citizenship application was denied.

The result is a riveting hybrid of memoir and socio-cultural interrogation as Lin retraces the rocky road towards equal marriage. When the UK introduced civil partnerships in 2005, Lin and his partner moved to the UK to make their relationship and their citizenship status official. For the first time in a decade, living together didn’t come with the threat of deportation for one for them.

Here, Jeremy Atherton Lin talks through the book’s key themes, including the way it invites readers to connect queer history with their own lives.

Nick Levine: Did writing the book make you rethink your attitude towards marriage in any way?

Jeremy Atherton Lin: My relationship to marriage has always been practical – it was the most resolute solution to our dilemma. We’re not the only people who were put in that position, and there are a bunch of other positions where it can also offer a compromised but effective solution. We don’t live in ideal ways and marriage, as an institution, does offer certain safety nets and comfort. It can make life easier for people.

When people started reading the book, I think I realised how important [this story] could be. Things seem so hopeless now, but there is joyfulness and a sense of adventure here. In a nutshell, we found love in a hopeless place. I’m never going to be grateful for unequal laws or an oppressive framework, but when there have been past structures that forced people to live outside of social convention, we can learn from the ways they found to navigate that. They can disrupt those social conventions in a positive way.

NL: It certainly made me rethink my attitude towards marriage. I’ve always been pleased that same-sex couples won the right to marry but felt ambivalent about the institution on a personal level.

JAL: You’re not alone. A lot of other writers and thinkers that I respect were like, “I wanted to be in the gay bar, but I don’t want to get into a gay marriage.” There’s almost a slight aversion to the topic. But I also don’t think that it’s fundamentally the main topic of the book in any way.

The book is really about the way we live together, about borders and border-crossing – whether that be the threshold over a house or apartment or a national border. And I think its relationship to the institution of marriage throughout is always a kind of questioning one. It’s asking whether we feel liberated by pushing for that kind of assimilation.

“My relationship to marriage has always been practical – it was the most resolute solution to our dilemma” – Jeremy Atherton Lin

NL: Is it also a book about identity? When your partner was undocumented, he seemed to lose some of his identity because he was living outside the system.

JAL: Yeah, and that sort of became its own identity. But I think that was partly because of his nature – he’s somebody that other people want to adopt. People were very maternal and protective towards him when he was undocumented. But in congressional debates [about same-sex marriage and unauthorised immigration], I don’t think they were picturing someone like my partner, who’s this sweet, fay, floppy haired, kind-to-animals sort of a person.

It’s kind of deliberate that the political debate in the book is so absurd and, like, inhumane. There’s a complete divorce between the debate and real people living their lives. And I do think there are parallels with the current situation in the UK, where trans people’s voices don’t seem to be invited into the debate about their own lives.

NL: Did it feel important to include the sex scenes? They aren’t the main thrust of the book, but they sort of highlight that your relationship isn’t a straight one.

JAL: I think I say very explicitly [in the book] that I wonder whether politicians and lawmakers are actually imagining this kind of explicit [gay] sex and feeling squeamish about it. Or is it so removed from their imagination and what they accept that it’s more of an identity-based thing that’s making them squeamish?

But absolutely, it’s always felt very important to include sex [in my work] as a kind of active resistance, because I do think that so many intolerant and unfair laws are, at their core, motivated by some kind of squeamishness around gay sex.

“The book is really about the way we live together, about borders and border-crossing – whether that be the threshold over a house or apartment or a national border” – Jeremy Atherton Lin

NL: Finally, what do you hope people take away from Deep House?

JAL: I’d like to encourage people to be interested in history as a kind of live thing. I feel like people say that they’re interested in queer history, but they don’t necessarily know how to enact that. What I was trying to do with this book, was animate experiences rather than find moments that are meant to be definitive, like the Stonewall riots.

I wasn’t trying to focus on any kind of outcome or turning point [in the queer rights movement] but to create a sense of being compelled by the mess. Because I think that once we get to experience some of that mess, it feels a bit more related to our own lives and where we are now.

Deep House by Jeremy Atherton Lin is published by Allen Lane, and is out now.

Leave a Reply